Residence R&A

House Alterations & Additions in Princes Hill - Victoria

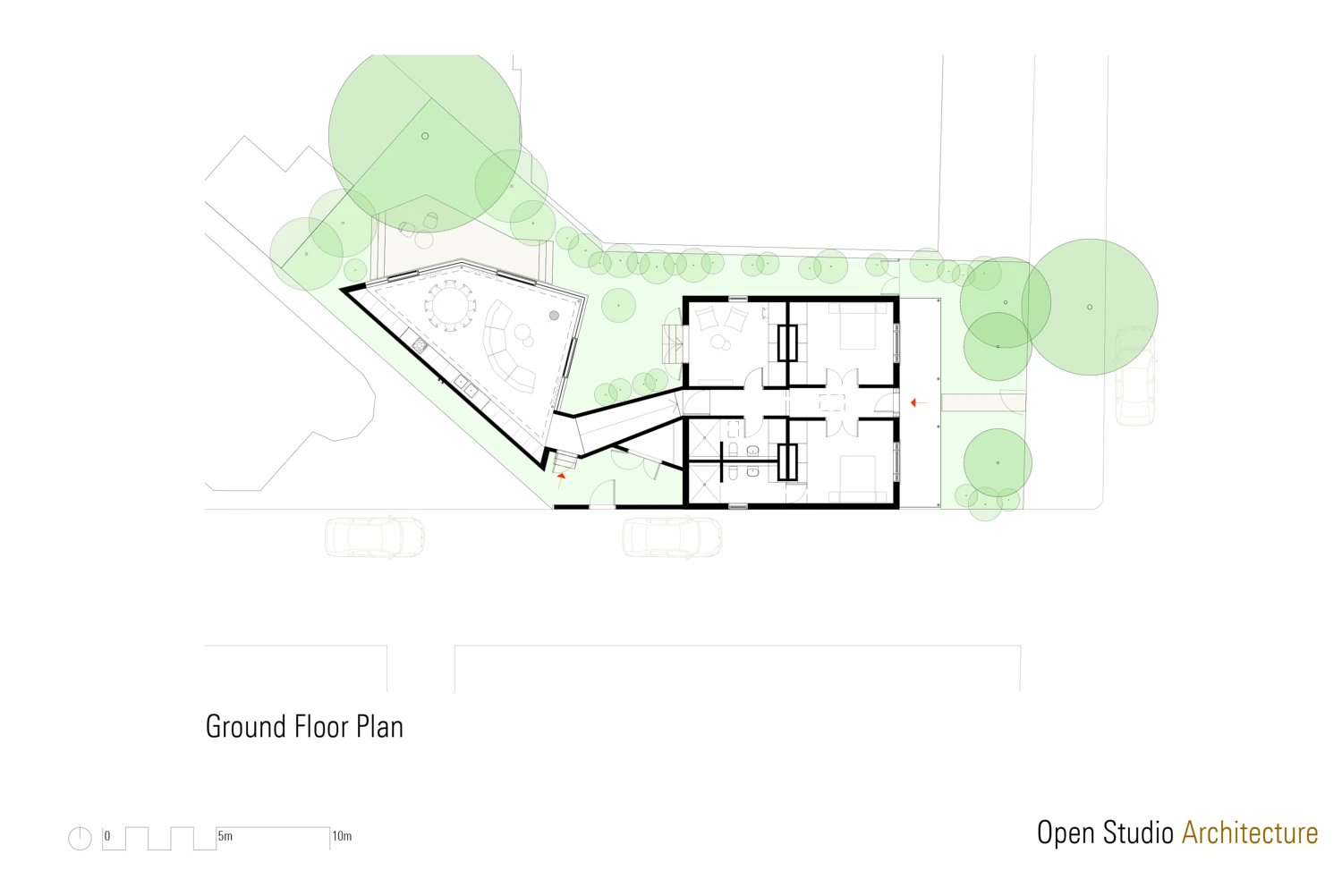

After years of living on an 11-acre property in the Dandenong Ranges, surrounded by native bush and an extensive perennial garden, our client decided to return to Melbourne. Searching for a home close to the CBD yet surrounded by vegetation, she discovered a single-storey Victorian residence in need of care. The unusual geometry of the site lent itself not only to a small but dense private garden around an existing Jacaranda tree, but also to the possibility of a carefully considered extension

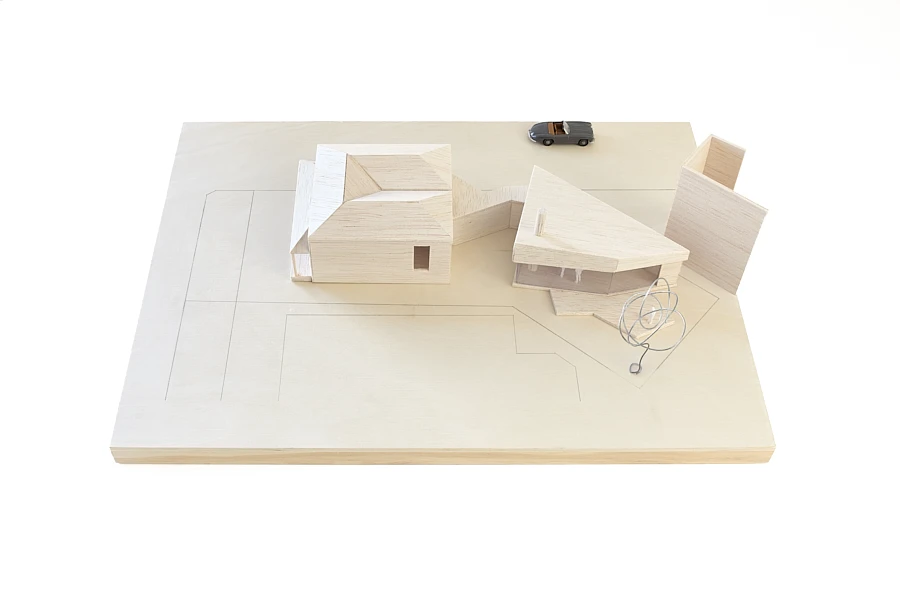

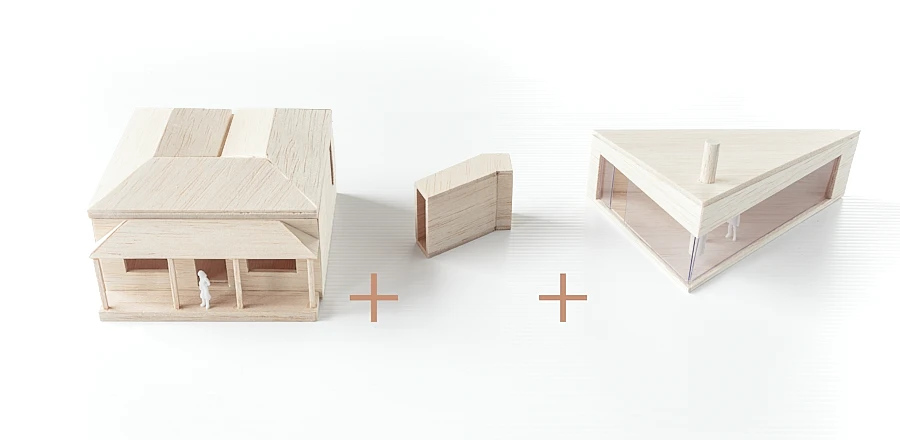

Working with existing buildings has always been central to our practice, and the dialogue between old and new is a recurring theme we explore. Often, the best approach is to link them gently into a single whole. This time, however, the most fitting solution was a radical separation, allowing each to stand independently

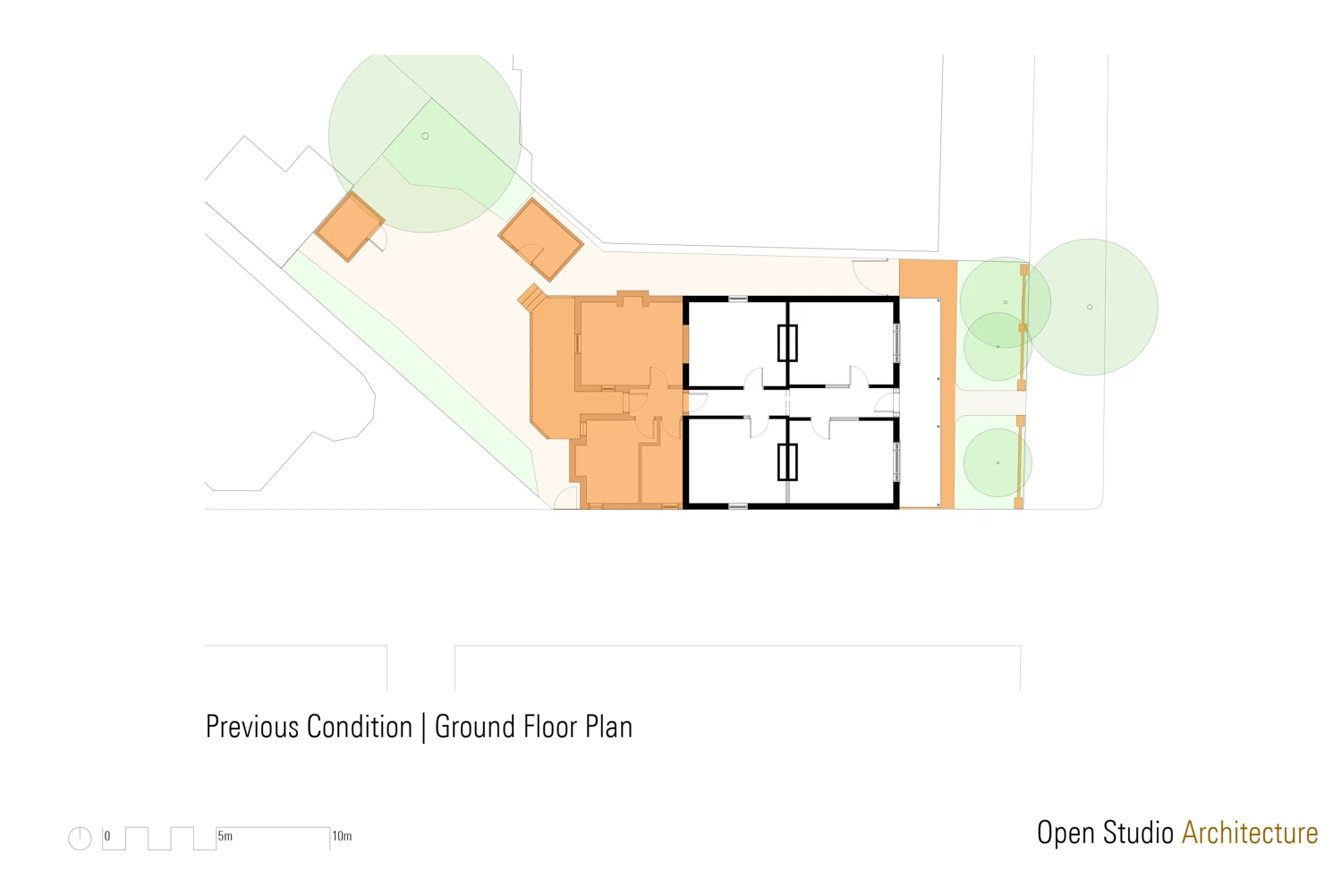

Old House

The existing dwelling was approached as a “found object,” transformed with restraint. It was reduced in size, repaired, and returned to its original logic—stripping away only poor-quality later additions while keeping as much of the solid original as possible. This was not erasure, nor a nostalgic restoration to an idealised past, but a careful act of reuse and repair, leaving visible the traces of time and use

The result is four generous rooms of equal size, arranged around the typical central circulation. One room became a bathroom and an ensuite, while the others were left largely untouched. New fit-out and joinery remain intentionally generic, allowing each space to serve as a bedroom, study, or sitting room as needed. With its solid brick walls and punched windows, the structure conveys a familiar, reassuring sense of solidity and shelter

New Pavilion

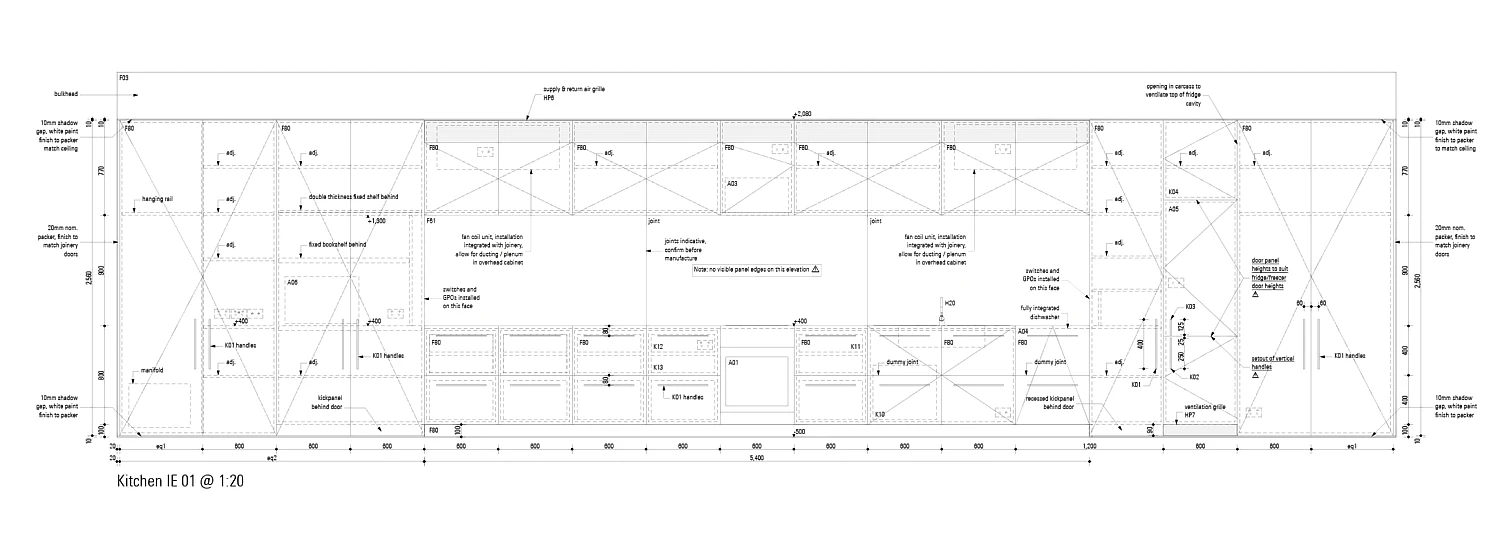

In contrast, a new volume, designed as an open-plan living-dining-kitchen, is a reinterpretation of the modern glass pavilion filled with natural light and connected to the surrounding landscape. Sitting under the canopy of the Jacaranda tree, the low pavilion opens onto the garden, giving the impression of being immersed in nature. Its irregular form negotiates the unusual footprint of the site and deepens the dialogue between interior and exterior

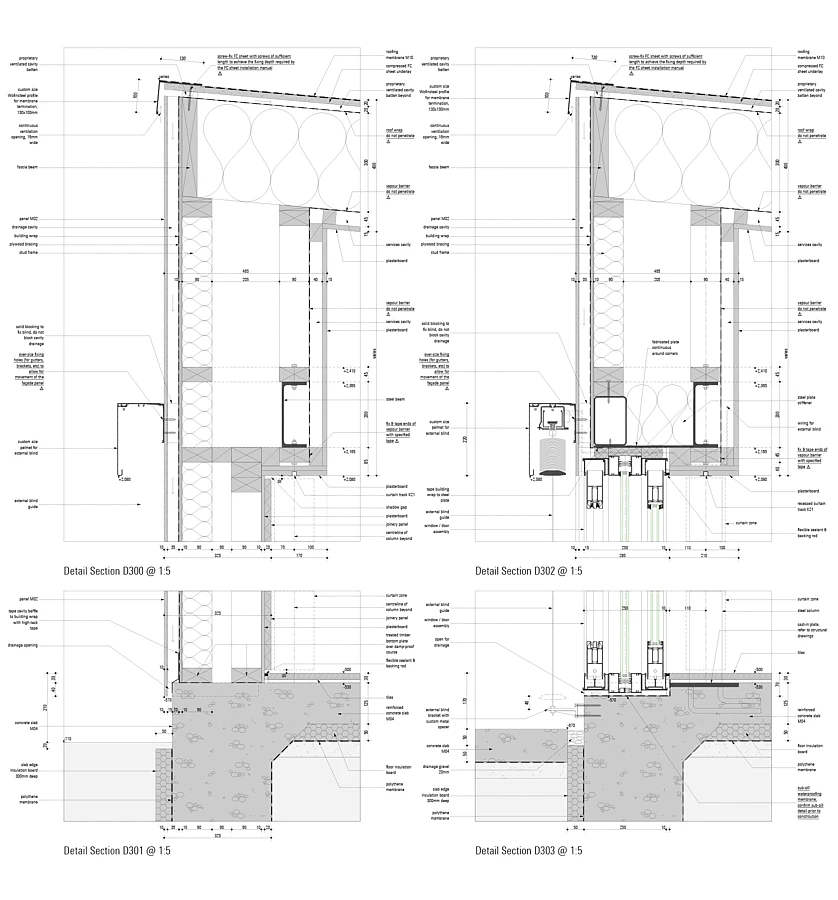

Interior elements such as the sloping ceiling, recessed kitchen, freestanding columns, and suspended fireplace are carefully restrained, while the glass façade—detailed with minimal junctions and glass-to-glass corners—reinforces this impression of openness and lightness

Yet this is not a glass envelope solely dependent on air-conditioning; rather, it is a deep façade—an assemblage of components working together to achieve appropriate thermal performance and interior light quality. It achieves a delicate balance between transparency and climate control, with internal curtains, insect screens, high-performance glazing, and external Venetian blinds providing the ideal solution for Melbourne’s unpredictable weather. Ultimately, a good building adjusts to its environment, and these adjustments can also be a source of pleasure, becoming daily rituals that make one feel more connected to the natural world

Link

An unusual passage connects the old building and the new pavilion. Enclosed, dark and muted, it is more than a means of circulation. It serves as a deliberate pause, an extended threshold between two conditions—the weight and familiarity of the old, and the lightness and transparency of the new. Lined in acoustic panelling and carpet, it is an extremely quiet and peaceful space, creating a moment of silence, of acoustic intimacy, a brief suspension. Within this pause, an experience of interiority and sensory uncertainty unfolds: slightly disconcerting, yet inwardly focused

While the design emerged intuitively, the work of Juan Fabuel on darkness has helped us better understand and articulate what is at play in this space. His writing speaks to a reconnection with darkness—a condition often dismissed by contemporary culture—and reminds us that deep shadow is essential. It dims the sharpness of vision and renders depth and distance ambiguous. It invites peripheral vision, tactile memory, and imaginative projection. This sensory dimming challenges the dominance of the visual and opens space for a more intimate, vulnerable, and uncertain encounter. As Fabuel observes, “In this darkness, the body listens. Awareness expands,” encouraging a more embodied, relational mode of engagement. Through this quiet uncertainty, the link becomes not only a spatial threshold but a moment of sensory reconnection

Garden

The garden, in turn, acts as an extension of the interior, weaving around the building to form a continuous, unfolding landscape. Smaller areas naturally emerge, each with its own quality, shaped by planting and light. The angles of the walls help define intimate pockets, like garden rooms, offering shaded spots and concealed nooks. But this is not a home in the country; it is an urban dwelling, with the city close by, adjacent yet screened out. By creating its own quiet place, the garden offers a beautiful, peaceful atmosphere. It has an intimate character and the sense of protection found in fenced or walled gardens (hortus conclusus)

The garden is contemplative, meant to be experienced from the interior, inviting reflection on the natural cycle and the circularity of time. And yet, it is also an active landscape for an engaged occupant, a place for enjoying gardening while experimenting with plants. It is not a fixed state but an ongoing, living process—mutable and transitory. The large Jacaranda is joined by a crab apple, golden rain, crepe myrtle, and forest pansy, underplanted with layers of perennials, shrubs, and grasses, all set against a background of passionfruit and Boston ivy. Textures, colours, scents, and gradations of light all define the ever-changing atmosphere

A House with No Centre

In its totality, the project deliberately avoids a sense of unity. It unfolds as a continuously evolving conversation between its parts, more like a Dadaist collage of fragments than a resolved composition. The old house and the new pavilion remain distinct, their differences unmediated. This deliberate juxtaposition allows tension to play out rather than seeking resolution

The residence resists a singular, unified experience. Its interest lies not in a predetermined form but emerges through use, revealing itself gradually as one moves through or around it. Functions sit apart like an archipelago—each island self-contained yet part of the whole. The project reveals an intriguing absence of a dominant centre, without a single focal point or rigid hierarchy. Instead, the experience is complex and layered, estranging the familiar and subtly reifying everyday moments

Project Data

| Site Area: | 350m2 |

|---|---|

| Floor Area: | 155m2 |

| Completed: | 2023 |

| Consultants: | Amanda Oliver Gardens (Landscape Designer) |

| Maurice Farrugia & Associates (Structural Engineer) |

Sustainability Data

| Orientation & Form: | prioritising retrofit and up-cycling of existing spaces |

|---|---|

| minimal demolition - restricted to thermally and spatially underperforming fabric | |

| new footprint kept to minimum | |

| layout maximising solar access and natural daylight | |

| space zoning | |

| Envelope: | designed for durability, longevity and minimal maintenance |

| thermal mass (concrete slab) to stabilise internal temperature | |

| thermal insulation levels exceed building code requirements | |

| double-glazed windows with thermally broken frames | |

| air barriers increase air tightness and manage moisture in building envelope | |

| facade cladding sheet layout defined by material sizes to reduce waste | |

| Energy: | net zero energy-ready house |

| natural cross ventilation via large openings fitted with insect screens | |

| adjustable, retractable louvres for external window shading in summer | |

| heating, cooling and hot water delivered by high-efficiency heat pumps | |

| no gas connection | |

| Water: | site rehabilitation, paved areas replaced with permeable landscapes |

| rainwater collection and use for wcs |